What would count as examples of ‘utter flatness’. List five things an artist might do to exploit the idea. In other words what kind of things might one put on a gallery wall that could pass for an abstract or figurative painting but also reveal themselves to be everyday objects?

In Greenberg’s essay ‘Modernist painting’ (1961), he argued that modern disciplines became more competent by criticising themselves. Disciplines needed to distinguish themselves from each other and this was achieved through self- criticism.

The purity and uniqueness of painting was that it was the only art form to use a flat surface. Modernist painting orientated itself towards emphasising flatness. The tradition of creating an illusion of real life through representation was not attempted, instead artists attempted to draw attention to the fact that viewers were looking at paint on a flat canvas surface. As Greenberg suggested, this flatness could never be a literal flatness but more of an optical flatness.

So, how could an artist exploit the idea of ‘utter flatness’? I will list 5 ways that I have discovered that artists have used and provide examples to show how this has been achieved. In my research, I discovered many methods to exploit ‘utter flatness’ used by artists produced pure abstraction. In relation to the research question I shall highlight instances where artists have created works ‘that could pass for an abstract or figurative painting but also reveal themselves to be everyday objects.’

1.VISIBLE PROCESS

An artist might produce a ‘flat’ painting by displaying to the viewer how the paint has been applied to the canvas. The viewer is aware that paint has been applied to a flat surface and brush/stick/trowel strokes are visible creating texture. Perhaps the most obvious example of being able to see the process of paint applied to a flat surface is in the art of Jackson Pollock.

Pollock was an Abstract Expressionist painter who used action and gestures to create his paintings. Jackson removed his canvas from the wall, placed it on the floor and dripped, splattered or dragged paint with sticks in curved non-geometric forms. The paint often hit the canvas from a distance layering string like patterns. In this purely abstract piece of art we are in no doubt that we are looking at paint on a flat surface and that it has been applied with the physical energy and expression of the artist.

2. MASS BLOCKS OF COLOUR

Artists may exploit the idea of ‘utter flatness’ in painting through the use of colour and in particular mass blocks of colour. Still, flat, 2D, stable shapes destroy the illusion of the canvas as a visual window and emphasise its surface. The best example of this can be seen in the art of Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko.

Rothko does not attempt visual representation in his paintings but instead using colour to convey emotional states. Unlike Pollock, Rothko creates flatness by painting still, hazy blocks of pure colour that appear to float on the canvas.

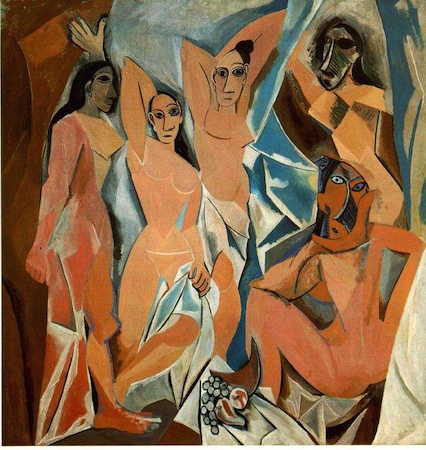

3. DECONSTRUCTING FORM

During the early 20th Century artists such as Picasso and Braque developed ‘Cubism’. This style of representing reality broke objects or figures down into distinct planes that showed multiple viewpoints at the same time within the same space. This effect emphasised the flatness of the canvas instead of creating an illusion of depth.

On first view, Candlestick and playing cards on a table (Braque) looks like a purely flat abstract painting. However, only after reading the title of the painting and looking closer can we start to identify the objects. The candlestick and the table appear fragmented and displayed from multiple viewpoints which creates ‘flatness’ in the painting.

4. SIMPLIFY

To exploit the ‘flatness’ of the canvas, artists could simplify their paintings using simple, geometrical shapes and/or lines using pure colour. The best example’s of paintings that use this method can be found in the minimalist movement. In the 1960’s artist Frank Stella took the idea of emphasising flatness to the extreme.

In Zambezi, Stella creates an expressionless, symmetrical, geometrical pattern using clean black and white lines. The design emphasises the fact that we are looking at a flat canvas by emphasising the corners and the centre of the rectangle. The gaps between the white stripes (black areas) are of a width that suggests the depth of the canvas and perhaps its distance from the wall (Anderson, 2011).

We can also look at the work of Paul Klee to give examples of how simplification can emphasise the flatness of the canvas. In Castle and Sun, Klee represents real objects through the placement of simple geometric forms.

Blocks of pure coloured squares, triangles, rectangles and circles create a mosaic effect. Unlike Stella whose minimalist style is purely patterns, Klee creates a subtle representation of a castle with the sun overhead.

5. EXPLOIT THE SHAPE OF THE CANVAS

The canvas has a large part to play in creating an optical flatness. Firstly, we can argue that artists can draw attention to the canvas as a flat surface by creating an infinite space that does not have to have a central focal point ( See Fig 1. and Fig 4.). Secondly, Andrew (2012) points out that traditionally artists have the canvas representing a window shape so that we, as viewers, look through it at an 3D image that creates an illusion of representational reality. Artists can break this window effect by altering the shape of the canvas.

Finally, artists can draw the viewers attention to the rectangular shape of the canvas and it’s flat surface by defining its shape.

In many of Hodgkin’s paintings he emphasises the contours of his abstract paintings. We are in no doubt that we are looking at a flat surface. Rothko also emphasises the contours of the canvas using blocks of shape and horizontal and vertical lines (see Fig 2.)

Reflections

I found this exercise fascinating and enjoyed learning about different movements when undertaking my research. I especially found a series of lectures by Jonathon Andrews very informative as they explored Greenberg’s theories in relation to various art movements. When viewing Modern Art, Andrews advises us to ask the question ‘What does it mean to do this?’ Rather than ‘What does it mean/ What is this picture about?’ which I have now taken under my belt!

List of Illustrations

Fig 1. Pollock, J (1948) Number 1 [Enamel, Matt and Gloss on Canvas] At https://www.jackson-pollock.org/number-1.jsp#prettyPhoto[image1]/0/ Accessed 03/12/2019

Fig 2. Rothko, M. (1959) Red on Maroon [Oil on Canvas] At https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/mark-rothko-1875 Accessed 03/12/2019

Fig 3. Braque, G. (1910) Candlestick and playing cards on a table. [Oil on Canva] At https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1997.149.12/ Accessed 04/12/2019

Fig 4. Stella, F. (1959) Zambezi [enamel on canvas] At https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/2001.542/ Accessed 04/12/2019

Fig 5. Stella, F. (1971) Narowla II [ acrylic, felt, canvas and paper collage on panel] At https://www.phillips.com/detail/frank-stella/NY010619/54 Accessed 04/12/2019

Fig 6. Hodgkin H. (1979-1984) Clean Sheets [Oil on wood] At https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hodgkin-clean-sheets-t06550 Accessed 04/12/2019

Bibliography

Anderson, J. (2012) The (spiritual) crisis of Abstract Expressionism: Mark Rothko. [online lecture] At https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3V1SLKsF0BE Accessed 02/12/2019

Anderson, J. (2012) Postmodern Strategies: The Canvas as an Arena: Jackson Pollock [online lecture]. At https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k7fodAy0jbU Accessed 02/12/2019

Anderson, J. (2011) The Fully Present Object: Minimalism – Jon Anderson [online lecture]. At https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RogfryPVWDk Accessed 02/12/2019

Greenberg. C. (1961) Modernist Painting Forum Lectures (Washington, D. C.: Voice of America), 1960. Viewed at http://www.yorku.ca/yamlau/readings/greenberg_modernistPainting.pdf

Joselit, D. (2000) Notes on Surface, Towards a Genealogy of Flatness in Kocur, Z. and Leung, S. (2012) Theory in Contemporary Art since 1985, 2nd Edition. Chichester:John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p102-117

Masterpieces of Jackson Pollock, Number 1, 1948. Viewed at https://www.jackson-pollock.org/number-1.jsp Accessed 03/12/2019

Tate Art Term – Cubism At https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/cubism Accessed 04/12/2019

Wolf, J. Introduction to Flatness at The Art Story. Viewed at https://www.theartstory.org/definition/flatness/ Accessed 03/12/2019